A Patent Application is the only available legal way to protect the work of an inventor.

Niarb always made ample use of Patents, since its main activity was to operate in the field of innovations.

From the start, Niarb suggested to all its customers (equipment manufacturers) a radical approach about how they must deal with innovation: Niarb always stressed the deep interaction between innovation and economic performance.

Niarb philosophy on innovation sounded truly revolutionary in the 60's, but is almost universally accepted to day, as a recent survey of "the Economist" proves without doubt. (Feb 20-26, 1999 issue).

Before looking at some enticing Niarb Patents it seems advisable to quickly consider he prose of "the Economist").

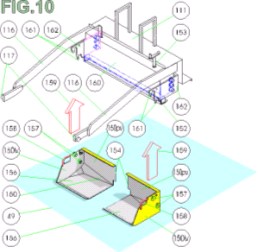

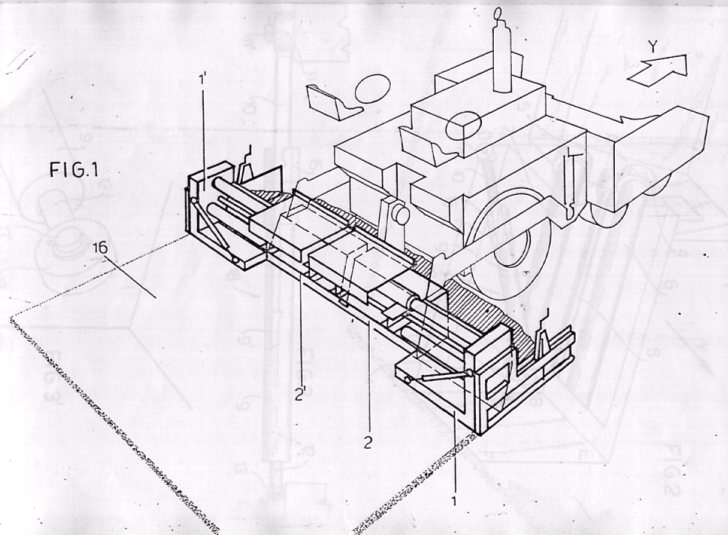

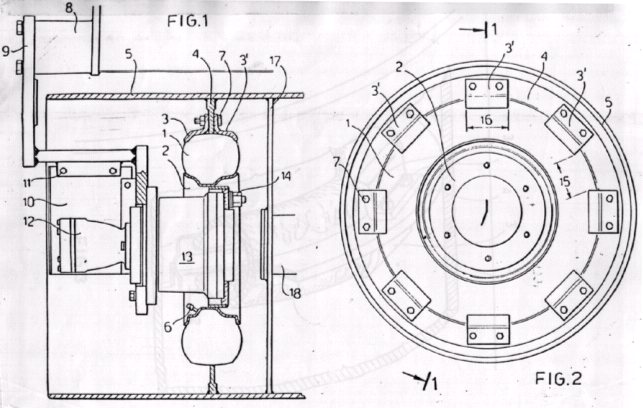

One of the many drawings included in a Niarb Patent Application describing a revolutionary "full Floating" extensible screed for asphalt (or concrete) pavers.

Innovation has become (at last, Niarb says) the industrial religion of the late 20th century.

Business sees it as the key to increasing profits and market share. Governments automatically

reach for it when trying to fix the economy.

Around the world, the rhetoric of innovation has replaced the post-war language of welfare economics.

It is the new theology that unites the left and the right of politics.

But what precisely constitutes innovation is hard to say, let alone measure. It is usually thought of as the creation of a better product or process. But it could just as easily be the substitution of a cheaper material in an existing product, or a better way of marketing, distributing or supporting a product or service.

Entrepreneurs (the most successful practitioners of innovation) rarely stop to examine how they do it. Most of them simply get on with the job of creating value by exploiting some form of change. They thereby generate new demand, or a new way of exploiting an existing market:

The drug firm that makes a generic version of a blockbuster ulcer pill is simply cashing in on the expiry of a rival's patents. All these are strictly business ventures, not innovations.

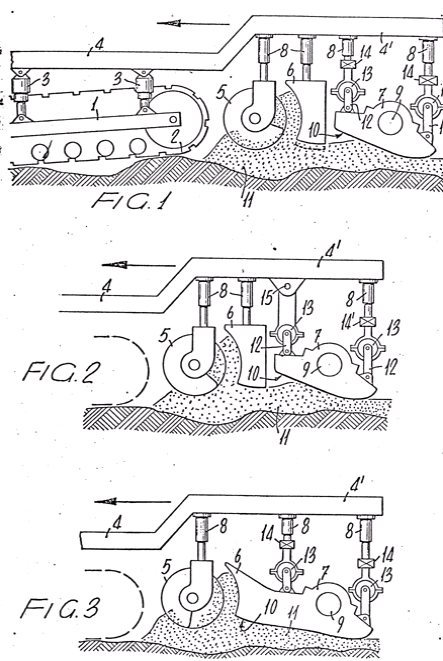

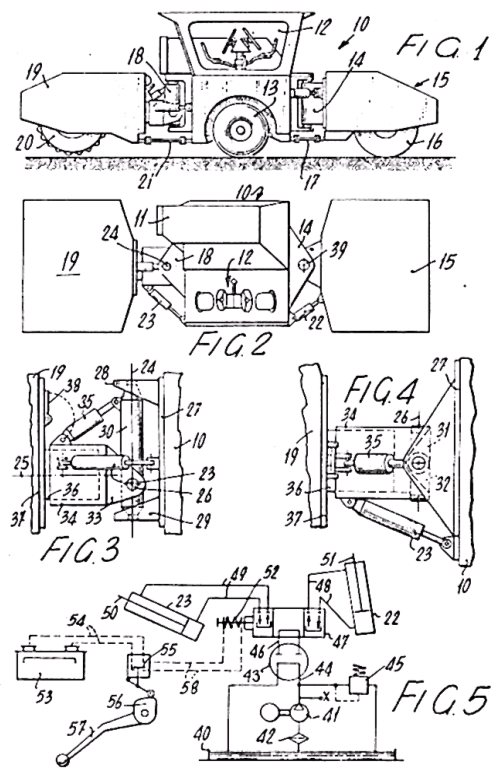

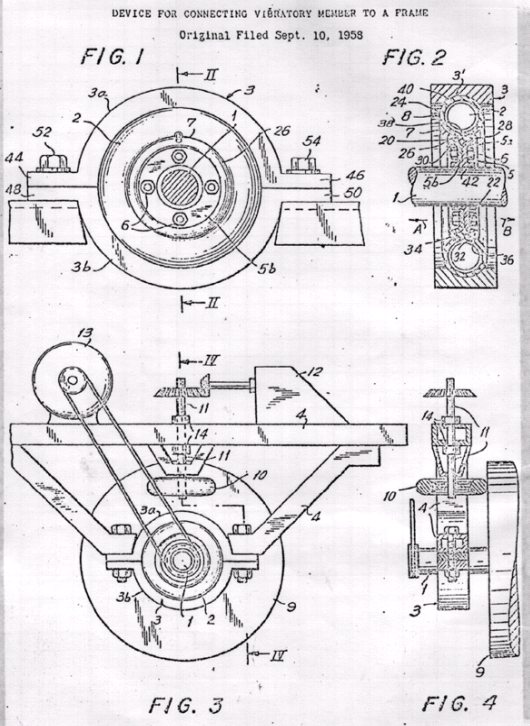

One of the first patents granted to a senior partner of Niarb in 1958

True innovations not only break the mould; they also yield far better returns than ordinary business ventures.

Two things set apart all organisations with a good record of innovation. One is that they foster individuals who are internally driven-whether they are motivated by money, power and fame, or simply curiosity and the need for personal achievement.

The second is that they do not leave innovation to chance: they pursue it systematically. They actively search for change (the root of all innovation), then carefully evaluate its potential for an economic or social return.

The irony is that officials, academics and entrepreneurs pay far more attention to the riskiest form of innovation (trying to exploit some science based discovery) than to the easiest and quickest type of innovation with which to turn a profit (capitalising on some unexpected success).

This may have much to do with the glamour of research and development-not to mention the large sums of public money that governments make available, directly through grants as well as indirectly through tax credits, for companies to do R&D.

Niarb opinion was, from the start, that innovation has more to do with the pragmatic search for opportunity than with romantic ideas about serendipity, or lonely pioneers pursuing their vision against all the odds.

Following the classic theories of economics, if you add more and more capital to a given labour force, or an increasing amount of workers to a fixed amount of

capital, the result will be successively smaller increases in output.

This is called the "theory of the diminishing returns".

It's a pure theory. In the real world things happen differently.

For instance, if the "law of diminishing returns" operates as it is supposed to,

why have returns on investment in America, Europe and Japan been higher in the second half of the 20th century than in the first half?

Why, for that matter, has the gap between the world's rich and poor countries widened rather than narrowed?

The theory says that where the stock of capital is rising faster than the workforce, as has clearly been true in the industrial countries since the second world war, the return on each additional unit of capital should fall over time.

Instead, it has risen over the decades rather than fallen, so something is amiss.

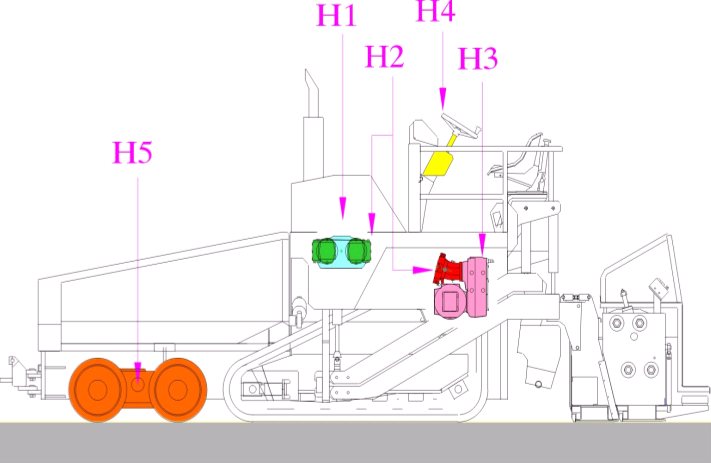

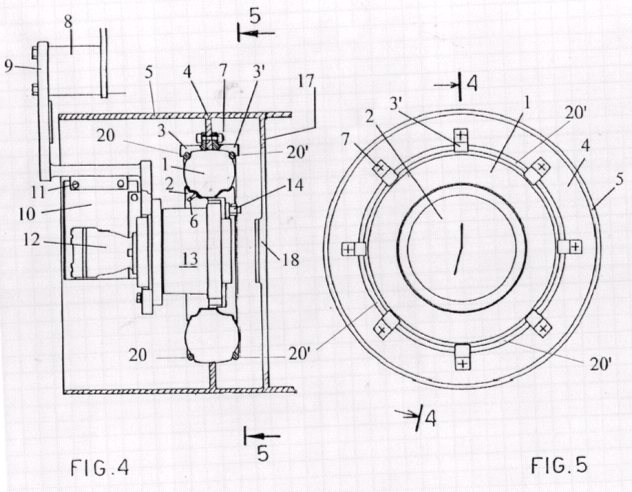

An interesting explanatory drawing from a Niarb patent application describing a "semi-floating" screed equipped with an enticing augers control system.

For want of a better explanation, that "something" is now reckoned to be technological progress plus other forms of new knowledge-in short, innovation.

In this more advanced scheme of things, innovation accounts for any growth that cannot be explained by increases in capital and labour. And although the return on investment may decline as more capital is added to the economy, any deceleration in growth is more than offset by the leveraging effects of innovation.

In other words, it is innovation, more than the application of capital or labour, that makes the world go round!

Furthermore, entrepreneurs have long accepted that innovation is anything but orderly and simple, and scholars are beginning to understand this too.

Governments, however, still tend to view innovation as a pipeline. If public money is stuffed into basic research in universities and national laboratories at one end, they reckon, new technology and commercial applications should pop out of the other.

Scientific discoveries do indeed sometimes lead to useful technologies which entrepreneurs incorporate into innovative products. The whole of the electrical industry can trace its origins to Michael Faraday's demonstration of electrical induction in1831. But just as often scientific theory lags behind practice.

For example, Wilbur and Orville Wright's airborne achievement on the sands at Kitty Hawk in 1903 begged questions of fluid mechanics not solved until Ludwig Prandtl's classic studies in Germany in the 1930s.

William Shockley had to invent a theory of electrons and "holes" in semiconductors to explain why the transistor he and his colleagues at Bell Laboratories had devised actually worked.

In real life, the innovation process is a cat's cradle of inter-relationships, a network of feedback connections.

The above page shows one of many explanatory suggestions prepared by Niarb to convince "Corporate Headquarters" to consider a "disruptive" innovation that could radically modify the market in favor of a true innovating technology.

Everybody loves the garage tinkerer who sells his brainchild to a big company and becomes a billionaire; and everybody sympathises with the plucky entrepreneur seeking venture capital for his little start-up company.

But in the theatre of innovation, they are a side-show.

Most successful innovations are born, bred and brought to market forcing them through well-established organisations, mainly large companies. The people who do this for a living (e.g. Niarb) are not so much entrepreneurs as "intrapreneurs".

For them, finding the money to support the development work may not be a problem, but getting the go-ahead from corporate headquarters often is.

How does a firm come up with an idea for a product that works five times better than existing ones, or costs half as much to make? Such quantum leaps in performance rarely come from tweaking existing designs. Nor do they emerge from listening to big customers, who usually just want steady improvements that yield wider margins.

Radical redesigns can have lots of teething troubles that spoil a customer's bottom line. Invariably, breakthrough innovations require a fundamental rethink. Sometimes they come from dusting off ideas that failed to make it in the past.

Quite often they stem from the sheer bloody-mindedness of individual engineers who refuse to abandon a pet idea and surreptitiously take it underground.

Coming up with mould-breaking innovations is totally different from making incremental improvements.

Important as they are, steady improvements to a company's product range do not conquer new markets. Nor do they guarantee survival.

To day everybody makes the distinction between "sustaining" technologies, which deliver improved product performance, and "disruptive" ones.

A statistical study of leading company failures has recently shown that in all cases the downfall of leading manufacturers was caused by some "disruptive" innovation from an upstart outsider.

The transistor was a disruptive technology for the vacuum-tube industry in the 1950s. The personal computer was probably the greatest disrupter of all time.

Dismissed initially as a toy, it single-handedly tore the whole of the mainstream computer industry apart, pushing even mighty IBM to the brink.

So even successful firms (and especially those riding high) often ignore breakthrough innovations at their peril.

It may be impossible to make such ("disruptive") innovations to order, but companies can do the next best thing: encourage the right conditions to allow radical ideas to be developed. (That's where and when Niarb comes right on hand!)

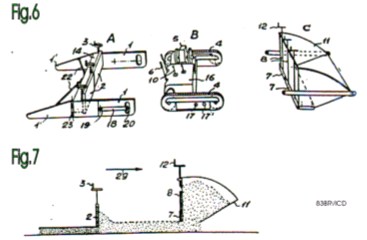

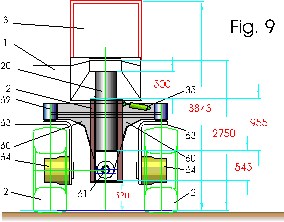

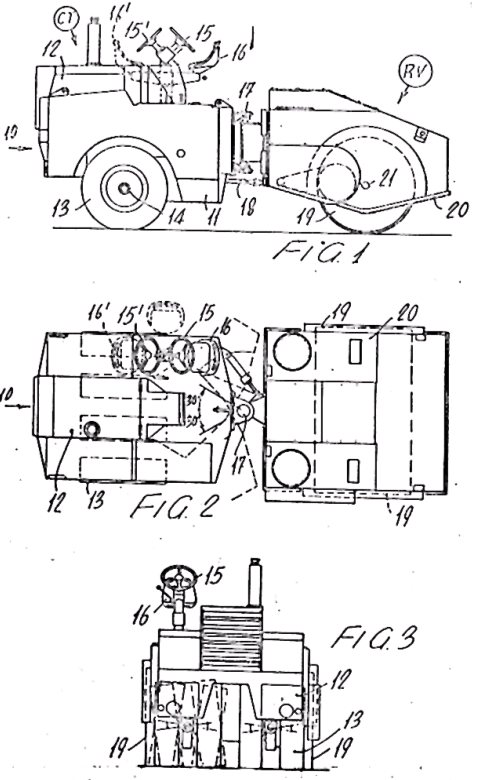

A schematic cross section of an embodiment of a patented self propelled Stabilizer showing the revolutionary single piston guide suspension system.

One thing is clear: all big innovations need to be championed and nurtured for long periods, sometimes up to 25 years.

Promoting innovation by peering into the gloom ahead, rather than behind, has become a top priority for smarter manufacturers.

"Intrapreneurs" reckon you have to start with around 3000 bright ideas to end up with four plausible programmes for developing new products and four development programmes are the minimum needed to get just one winner. The first thing to do is create a corporate culture that allows ideas to blossom.

"You have to kiss a lot of frogs to find the prince," says an old joke, "But remember, one prince can pay for a lot of frogs."

Moonlighting, however, is only for ideas in their early stages of development. To commercialise an idea successfully, a number of different stages must be completed, each more difficult than its predecessor (see chart 4). Failure to complete any one of them can wreck an innovation's chances.

Successful innovators agree that at least the first stages cannot be managed like an ordinary business. A bean-counter mentality will quickly wreck even the most vibrant breakthrough culture. So the environment in which innovations are fostered and nurtured should be at least culturally, if not physically, well apart from the corporate offices.

One trick that has worked for some firms is to create the equivalent of the "skunk works" pioneered by the Lockheed Aircraft Company in the late 1940s.

This is usually the wrong time to issue a Patent Application. Niarb does it much earlier and the related investments are huge:

Engineers working inside this secret little laboratory-cum-workshop, kept off-limits to all but the most senior Lockheed managers, were encouraged to break company rules wherever necessary. Above all, they were expected to ignore the official procedures demanded by the Pentagon.

The result was a stream of mysterious spy-planes and supersonic bombers that set new standards for performance, ahead of schedule and below budget.

The skunk-works element that innovative firms value most is freedom from bureaucracy. Sometimes the innovators are even given the freedom to transform their pet projects into small businesses without recourse to the parent company's production, marketing and finance departments. That was how IBM, steeped in a bureaucratic tradition of making large corporate computers with fat profits, managed to break into the leaner, meaner personal computer business-and thereby survived when many of its contemporaries did not.

To do so, however, IBM had to create a skunk works at Boca Raton Florida-just about as far, both physically and culturally, as it could get from its corporate headquarters at Armonk, New York.

Summing it up, Niarb was founded to become the "skunk-works" of everybody.

All Road Construction Equipment Manufacturers requiring a fully independent "think-tank" to develop radically new devices could consider Niarb from the start their efficient R&D partner.

Furthermore Niarb always studies and develops radically new machines and plants, following all "back-feed" it gets from the job-sites, so many Construction Equipment manufacturers can help themselves directly out from the large "stock" of patented inventions that form the actual Niarb intellectual asset.

Let's now go quickly through the long list of Niarb Patents mentioning some of their official titles and showing a few related drawings only.

... to be continued...